The Rule of St. Benedict is just boring. There’s really no way getting around that. I’ve tried to drum up a compelling anecdote, but…I’ve got nothing. And no wonder—The Rule of St. Benedict is a handbook on how to be a monk, so you might expect that it’s a little dry.

It dictated every aspect of life in a Medieval Christian monastery: what you ate1which was not a lot, when you slept2also not a lot—and only a few hours at a time, how you prayed, and when you worked—everything.

Having every moment of your life planned out sounds sort of hellish. But hidden behind this plan—this plan for every minute of every day—there’s a beautiful idea.

Every moment of the day is orchestrated because every moment is meaningful. Every moment matters.

And that’s really what the monastic life is about. Every moment is filled with purpose, and every task, no matter how trivial, is sanctified, for being a part of a life that is set apart for a higher purpose.3Yes, I am romanticizing a lifestyle that probably didn’t feel so romantic to someone who never got enough to eat or enough sleep and didn’t leave the four walls of the monastery for years on end. But I’ve come to believe that romanticizing life sometimes is good, and even necessary. Also, all the asceticism of the monastic life was purposed to detach the self from the world in order to achieve closeness to God. And there’s nothing so romantic as the beatific vision, to be honest.

It’s more than a schedule or agenda, it’s a ritual.

Ritual gets a bad rap these days. It’s used as a derogatory term for “meaningless rules.”

But it’s actually quite the opposite: a ritual is a pattern that makes meaning. It’s like a living work of art.

I love this idea, of making everything in your life mean something, have a value and a significance, if not a purpose.

But it’s an overwhelming idea, and it can create a lot of anxiety about having waste—wasted time, wasted space, wasted resources. I can’t imagine that there was much waste in an ideal Benedictine monastery, where every person, moment and utensil was always accounted for. But it’s harder to make everything count when there’s no rule book.

Then again, as it turns out, it’s possible to flub this up even with the rule book

Monasteries very frequently fell short of St. Benedict’s ideal. The story of Christian monastic history is one of reform: monks were ever slipping towards greater laxness. And after they had forgotten their original fervor, and apparently misplaced their rule book, a reform movement would inevitably spring up and reestablish the monastic ideal.

A cloister of one’s own

A few years ago, I embarked on my own reform movement…of sorts.

A year out of college, I was appalled at the depths to which my productivity had fallen. I had a million things in mind that I wanted to write. For the first time in years, I had some free time to work with.

But I must tell you, I was deceived in the words of Virginia Woolf, who, in A Room of One’s Own, wrote:

A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.

Sadly, it takes a deal more—because I had both and felt like I was writing even less than while I had been an impoverished, overworked undergraduate.

And so I, following in a time-honored tradition, deduced that this must be the fault of modern technology. The real problem was the internet. Naturally.

And my solution seemed elegantly simple: just don’t sign up for internet service. So that’s what I did when I moved into my first apartment.

Three hundred and sixty-five days without internet

I hadn’t intended to stay internet-less for a whole year, but when I hit that mark, I decided to take stock of what I had learnt, because living without internet hadn’t played out the way I had anticipated.

Yes, I was as surprised as you are.

I had naively assumed that the void left after removing distractions from my life would naturally be filled with productivity.

This was not what happened.

I was without internet. I had no cable. And for a few months I even had no TV or DVD player.

But I still didn’t know where my time was going—because I definitely wasn’t using it to be productive.

The moral of this story is laziness will find a way.

It had seemed so easy and convenient to pin my procrastination on the internet, but I can take some comfort that I am certainly not the first to ascribe an age-old problem to the latest technology.

So going internet-free hadn’t solved the problem I was looking to solve—but it wasn’t a totally failed experiment either.

Going without internet really just removes a set of distractions.

You can go find yourself some new distractions—but while you’re unconsciously looking for new ways to waste time, you might find yourself in a bit of dead air.

And dead air can be very helpful.

If you have a constant stream of media keeping your brain occupied, it never has a chance to take a breath and lead you somewhere interesting.

This is not news, I know. We all already know this.

If you want to actually get things done, it’s not actually enough to turn everything off.

Once you give the ideas room to breathe again, and it comes time to make those ideas reality, it’s still up to you to take the initiative, make a plan, and get to work.

At the time I was disappointed in myself, that I hadn’t really seized the opportunity I had created.

But that didn’t go on forever—and that wasn’t the whole story.

The idle valley

Eventually boredom set in. And then the boredom led to something.

I would start working on something (but usually not the thing I’d intended to get done in the first place). And then my productivity would gradually begin to rise.

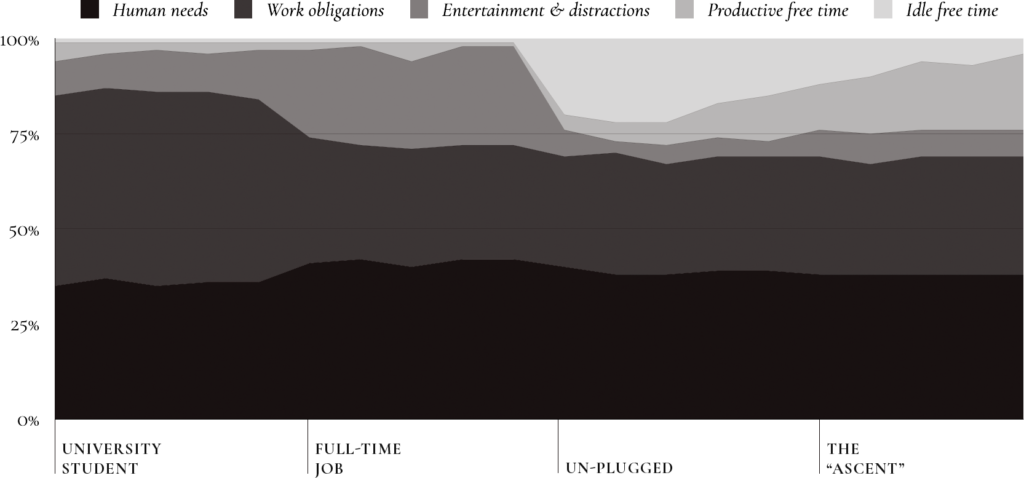

I call it “idle valley.” More free time and fewer distractions initially leads to a whole lot of nothing, as you descend into idle valley. But eventually, after doing nothing for long enough, your productivity begins to rise again, once you’ve refocused on a new project (or picked up an old one).

Figure 1. Idle valley

It took me a while to realize this was happening during my first internet-free year, because it can take a while to come back out of the valley. (It was maybe two or three years.) But it’s also because I wasn’t productive in the ways that I had hoped to be.

Instead of picking up old projects again, I ended up stumbling into a few entirely new creative projects that I probably would have never fixed on before my journey through idle valley.

Over the next few years, I picked up calligraphy, started learning web design and dabbled in graphic design. Then followed film photography, jewelry making, candle making, and book binding (look, it was a lot of free time, okay).

A lot of these, rather than being serious projects, served as “creative cross-training”4I don’t know if anyone else has already decided that this is a thing, but if not, I’m saying it’s definitely a thing. and as I geared up for returning to more serious projects.

This wasn’t the route I’d have chosen to take. I’d have rather just jumped straight into the projects that were most important to me. But I know that I’m a more well-rounded person and creator because of them.

And it also gave me a greater understanding of what factors do and don’t have a bearing on my productivity, or lack thereof.

The answer isn’t always just stop procrastinating. Sometimes it’s just stop. And then something will start on its own.

Interestingly, Christian monastic reform would also occasionally lead to surprising creative efforts.

The Cluniac reform in tenth-century France produced a monastic order that thrived for centuries. The Cluniac order is especially remembered for its magnificent Romanesque architecture5The basilica at Cluny was remodeled several times. It was at one time the largest church in the world. and excellence in Gregorian chant.

Meanwhile, monastic reform spread to England, where it took on its own flavour. Two of the leaders of the movement were reportedly handy at gold- and silversmithing. And one of these, Bishop Æthelwold of Winchester, ensured that the monastery at Winchester became a major site of book production. The books produced at Winchester were exquisitely crafted, and arguably the greatest surviving example of these is St. Æthelwold’s Benedictional, which he commissioned.

I should probably stop and say that I’m not suggesting that lazy ninth-century English monks were storing up energy for the coming resurgence—but I think it’s worth noting that ebbs and flows are a part of life, on a grand scale, as well as in the minuscule.

Sometimes the answer is to fight the tide, but I think sometimes it makes more sense to go with the flow—or stop awhile and wait for the next wave to come around and catch you up.

Such good encouragement. I love the idea of the sacred in the day to day.

Thank you!

Best one yet!

Wow, thank you! I didn’t expect that!