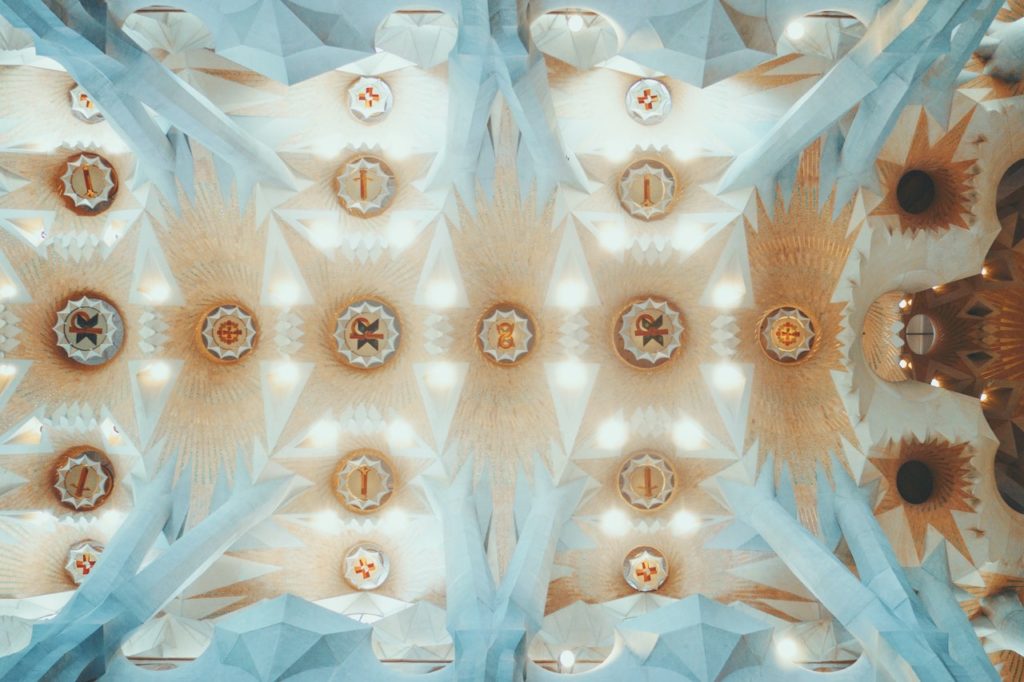

In 1883, Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí began work on the Basílica de la Sagrada Família, in Barcelona, Spain. To simply call this structure “a cathedral” feels somewhat misleading. It does look like a cathedral—but like one you might find at the bottom of the ocean or on the surface of the moon.

It is utterly otherworldly. The level of detail is overwhelming and the shapes are unexpected yet fluidly organic.

Gaudí completed many buildings in his career, but la Sagrada Família—which he worked on intermittently for the last forty-one years of his life—is unequivocally his greatest legacy.

Yet at Gaudí’s death, the cathedral was at most only twenty-five percent complete.

An unfinished masterpiece

A project left unfinished is not the logical place to end a discussion on perfection. But I share this story to illustrate how much can be achieved even when so much is still left unfinished. Gaudí’s incomplete masterpiece shows that completion is not always necessary in order to create a truly inspired work of art.

But Gaudí did not spend his entire career on this single unfinished project—he completed many others while he continued working on la Sagrada Família. He seemed to be very comfortable with the incompleteness of it: When asked about the delay, Gaudí was supposed to have said, “My client is not in a hurry.”

His client was God.1Gaudí was a devout Catholic and became known as “God’s architect.” He was made “Servant of God” in 2003, and there has been ongoing interest in his beatification and ultimate canonization.

Of course, Gaudí never intended to leave the structure incomplete. I have to wonder if the reason he did not agonize over it, was that he knew that the structure was not devoid of value simply because it was unfinished.

Created things have a way of taking on a life of their own, once released into the world. And the basilica has already begun its life—a life of perfectibility, moving ever closer to completion.

There is no hiding a cathedral away in a studio until perfected, like a canvas or manuscript may be. And all this while the people of Barcelona have been living with la Sagrada Família. Life cannot be bothered to wait for art.

Architects have since returned to Barcelona, hoping to finish Gaudí’s work by 2026—the centenary of his death. But the cathedral’s reputation is already immortalized and the city is continually flooded with tourists who come to see the church.

The perfection of imperfection

This idea, of a thing that is perfect in its imperfection—being “perfectly imperfect” gets thrown around a bit—no doubt a backlash against the infamous perfectionism I talked about in Chapter 1. But the concept goes back quite a while. Italian philosopher Lucilio Vanini2 Vanini based his assertion on earlier scholars, such as Greek philosopher Empedocles. first articulated this as the Perfection Paradox: true perfection is achieved in a state of imperfect perfectibility.

I like Vanini’s solution (if we can call a paradox a solution), but where does this leave us, in answering the question from Chapter 2: How do we know when we are finished? How are we ever to know when we have reached the finishing point? If we aren’t striving for perfection, then what are we striving for?—what ought we to strive for?

Throwing about the term “perfectly imperfect” may be vaguely “encouraging” but it isn’t very helpful. I want to know how to work hard with imperfection, not how to give up on perfection.

And even though I admire Gaudí for the way he worked on la Sagrada diligently and patiently for years, never feeling rushed, I also admire that he finished many other buildings in his career. Along with his completed portions of la Sagrada Família, six of his buildings are part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

I don’t know how Gaudí navigated each of his projects, how he decided when to keep working and when to finish, but I’ve created my own approach of finding the point of “imperfect perfectibility” in a project, which I’d like to share.

A method for finding the imperfect end

To begin with, we must return to Aristotle and his third and final definition for perfection, from Chapter 1:

things which have reached their fulfilment [sic], when it is worth while, are called complete, for they are complete by virtue of having attained their fulfilment.3Quoted from Metaphysics: Books Gamma, Delta, and Epsilon by Aristotle and Christopher Kirwan (1971).

The word fulfillment suggests that something can be perfect, not because of itself, but because it is part of something greater than itself. There is a greater purpose.

Thirteenth-century Italian friar and Doctor of the Church St. Thomas Aquinas also had a three-part schema of perfection, and his third definition emphasizes an external end goal. In his Summa theologiae, Thomas states,

thirdly, perfection consists in the attaining to something else as the end.4Quoted from Prima Pars, Question 6, Article 3, The Summa Theologiæ of St. Thomas Aquinas, Second and Revised Edition (1920). Literally translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province. Online Edition Copyright 2017 by Kevin Knight. Read more here.

How many imperfect people have accomplished great things, how many imperfect endeavors have yielded incredible results, and how many imperfect efforts have made the greatest difference?

Thomas Aquinas didn’t know this at the time he wrote these words, but the very book he wrote them in is a testament to this principle: that sometimes perfection is about the effects rather than the causes. The Summa theologiae is an immense work, written as a sort of textbook for theologians, and one of the foundations for Thomas’s title as a Doctor of the Church—yet the Summa was left unfinished at Thomas’s death.

Perhaps focusing on end results sounds too utilitarian for creative work. Art isn’t about use or function, is it? But for me, if I step back and think about why something has to be “just so,” it’s because there is some greater effect I am hoping to create. There is some effect that you hope your work will have on its audience.

Even in the fine arts and—and especially in design or copywriting and other creative fields—we’re talking at some level about cause and effect. I’ve come to the conclusion that whenever I become hung up on imperfections to an excessive degree, I’m most likely thinking about the cause more than the effect. It’s a “forest for the trees” situation. So for me, the solution is to keep the effect in mind and to remember that excellent effects do not require perfect causes.

This is your brain on unfinished artwork

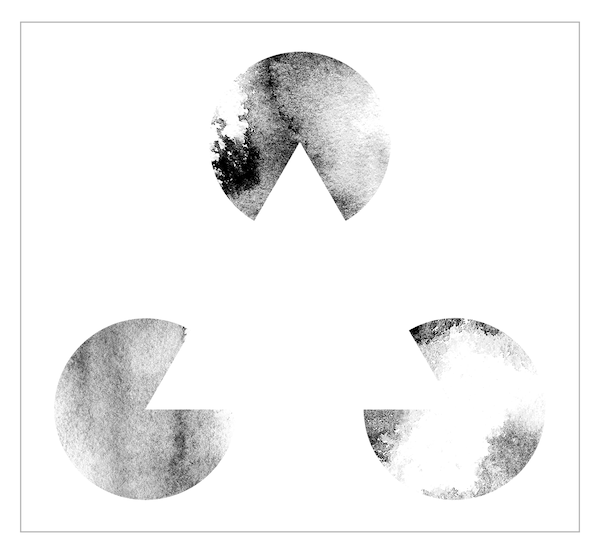

There’s even a field of psychology that suggest your audience doesn’t need you to fill in all the gaps for them. Gestalt psychology was developed in the early-twentieth century by Max Wertheimer in order to describe how the human brain interprets certain types of visual phenomena.

The easiest way to summarize Gestalt psychology is “the whole is more than the sum of its parts.” The brain will always look to connect the dots, in order to make sense of what visual information it receives.

For example, in the following illustration, it is impossible to not see the implied triangle created by the three incomplete circles. We mentally fill in the gaps. This is called reification. And we see the effect of the whole, before we take note of the individual parts. This is called emergence.

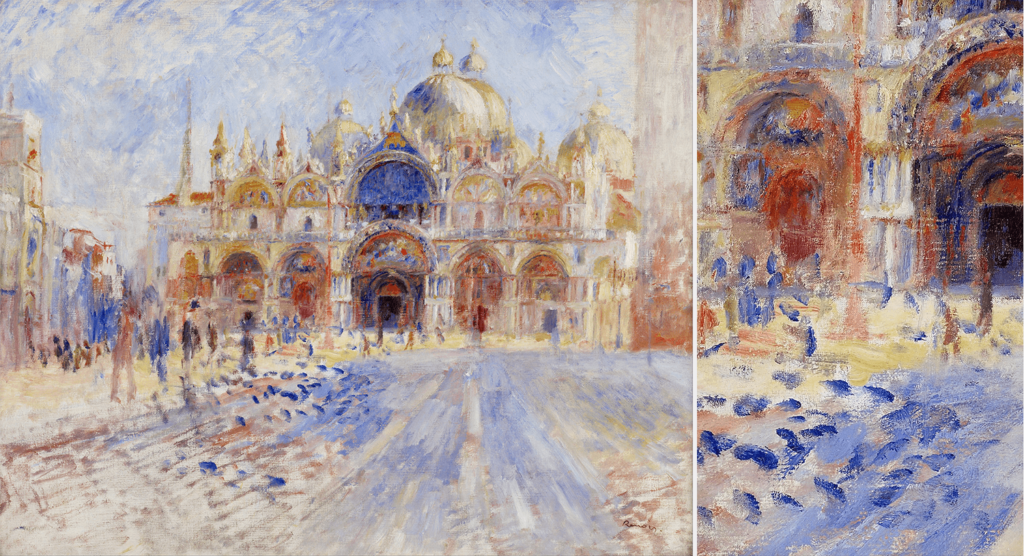

These principles are incredibly relevant for the visual arts. Much of M. C. Esher’s artwork plays with the Gestalt laws of figure vs. ground and multistability, the same way that optical illusions do. And the phenomenon of emergence is very similar to the experience of viewing impressionist artwork.

Impressionistic painting is a very different experience when viewed up close versus when viewed at a distance. These pieces by Claude Monet and Pierre Auguste Renoir exemplify the incredible power of the whole over the sum of its parts—or in this case, brush strokes.

Finding the end

But even if you are not an impressionistic painter, I think there is a lesson to be learned here that extends to other creative fields.5A similar effect can occur in writing and speaking, for example. One of Aristotle’s three rhetorical appeals for crafting persuasive language was logos. Logos requires presenting a logical argument (such as a syllogism) but with one piece of the equation left missing—a piece which the rhetor knows his listener will be able to supply—so that the listener can bring in their own knowledge and, in a way, complete the argument for themselves. I share the example of Gestalt psychology to show that letting go of complete control over the perfection of your work may require placing just a little extra faith in your audience. But that may be a good thing—a sort of invitation to your audience to engage with your work more closely.

It’s riskier, and in many ways it’s harder, than crossing all the t’s for yourself, but its effects could very well be infinitely greater, if we let ourselves let go of little flaws in favor of focusing on the greater effect we want to achieve. Imperfect excellence is not only more attainable than perfection, but I believe it is also more valuable, more powerful.

When we set perfection as our goal, we are striving for a low bar which we may never reach, distracting us from the higher things that may yet be in our grasp.

To create excellent, effective, and meaningful work does not require perfect efforts or even complete results, because the whole of your creative work is more than the sum of its parts—perfect or imperfect as they may be. The truth is that there are so many things more important than perfection. Why strive for perfection when there is something so much greater to strive for?

You were made for bigger things—things that cannot wait for perfection.

Perfect! 🙂 I mean…uh…very nicely done.

Haha. Thank you very much!