In southeastern Germany, in the state of Bavaria there is a Benedictine abbey dedicated to St. Walburga. And in the abbey, to this day, there is a small collection of drawings made around the year 1500 by an unnamed nun.

These drawings stick out like a sore thumb, among the rest of the abbey’s collection of medieval art: the technique is not that of a professional artist and the subject matter is not that of most medieval religious artwork. As Jeffrey Hamburger describes them,

Their awkward technique and idiosyncratic imagery indicate the relative isolation in which the nuns worshipped and worked.1I was first introduced to the drawings from St. Walburga, Eichstätt by Jeffrey Hamburger’s book from which this is quoted: Nuns as Artists: The Visual Culture of a Medieval Convent, U of California P (1997), page 10.

They are evidently the work of an untrained yet imaginative woman: the drawings are not aesthetically pleasing by modern standards (perhaps not by medieval ones either)—some of them are even grotesque—but it is clear that great care went into formulating the unique scenes.

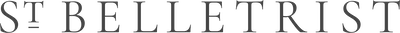

Drawings, by an unnamed nun, from the Abbey of St. Walburga, Eichstätt, Germany

The scenes shown are highly symbolic, but in very unconventional, creative ways—the trinity is shown living inside a house shaped like a heart. A is rose blooming, with a scene from the life of Christ at its center.

I began wondering how a nun, untrained in artistic technique and isolated in an abbey could have come up with such original creations.

It’s hard to imagine, from a modern perspective, just how isolated the lifestyle of a 16th-century nun could be. Already for all people of the late Middle Ages, life was lived within a much smaller circle of information and communication.

But for a nun, the circle was still smaller: not just a village or a town or a county, but a single complex of buildings. St. Benedict, in his regulations for monastic life, even discouraged community members from sharing stories about the outside world when they returned from journeys. It’s hard to imagine even desiring that level of isolation from the world, much less living in it.

But that was the purpose of the monastic life: to live as if no longer on earth, but in heaven already.

How then, had this unnamed nun achieved such singular work?

Then I realized that this question was an answer to itself: a nun isolated from the most popular techniques and subject matter and artwork of the time would have no choice but to create unique work.

This story of the odd drawings by an untrained unnamed nun in 16th-century Bavaria has stuck with me, because of the lesson embedded in it.

There is value that can be found in confinement.

It seems almost impossible to draw any kind of comparison between medieval monastic life and our own lives—the differences are enormous. Nevertheless, we all have our own forms of confinement to grapple with.

Alone in this together

Right now, we are all participating in a paradoxical shared experience of isolation. But from childhood timeouts onward, we all have our different experiences of unwanted confinement.

And if how you live has any bearing on how you create, then our work and work processes are changed by these experiences—not necessarily always for the better, but not always for the worse either.

And that is what I want to talk about in this three-chapter Cycle. I hope these conversations will be germane to current experiences, but I also hope to consider how confinement is not a COVID-19 issue per se.

There’s nothing new under the sun, even in what seems unprecedented. Which means there’s always something to learn from the past about the present.

My own private Stockholm

I actually started thinking about this topic of confinement several years ago. I’d found myself in a place that, all things being equal, I wouldn’t have chosen for myself. I had moved for a job that I loved to a city I once told myself I would never live in.

At first, it was only supposed to be for three months, and then three months turned into a year, and then that year turned into several years more, and still I had no plans to leave. It was my free choice and a choice I made confidently.

But I so wished for the place where I had chosen to be, to become the place where I wanted to be.

I began thinking about Stockholm syndrome, that strange psychological twist of fate that turns prisoners into accomplices. Captives become paradoxically devoted to their captors.

The term was coined following an unsuccessful attempted bank robbery, which would probably have slipped into obscurity were it not for a peculiar turn of events.

On 23 August 1973, two men took the Kreditbanken in Norrmalmstorg, Stockholm, and along with it four bank workers, held as hostages in the bank’s vault. Five days later, when the ordeal came to an end, the hostages emerged from the bank anxious above all else for the well-being of their captors.

It’s a hard reaction to make sense of, but it’s actually a psychological coping mechanism or survival tactic. When a hostage’s whole world shrinks down to the size of a single room or building, and when all authority devolves upon the captor, it can actually be in the hostage’s best interest (for the time being, at least) to endear themselves to the person who holds the power.

From this perspective, it’s really quite remarkable: this unintuitive yet instinctive response to unpleasant situations—to embrace the circumstances.

And in a weird way, it was something I found I wanted (odd though it sounds): to be able to fall in love with where I was. I really wanted for the place where I was supposed to be, to become the place where I loved to be.

The Stockholm project

I thought a lot about how to go about this change. The approach I took was to become a collector. I began searching and choosing and making note of—places and stories and ideas and novelties.

I collected the things that jumped out at me, however small and insignificant.

It was a project that started very inauspiciously and unconsciously. My very first collection (if you can believe it) was names of streets. Streets with women’s names. Streets named after capital cities in the United Kingdom. Streets named for places in Virginia.

Twenty-four assorted street names, collected for no reason in particular

It was a silly exercise, but it was a start. And I then moved on to less inane collections: I collected places I loved, places I wanted to visit. I collected beautiful houses and interesting buildings. I collected stories about people who had lived there long ago. And then I began collecting hobbies—things I brought there myself.

I’ve since realized that all of these different collections served two basic purposes: they helped me to look more closely and to reach further for inspiration, for things to love, for a life that I could make my own. I’ll be talking more about these two in the following two chapters.

Stockholm in retrospect

It’s been several years since I began the Stockholm Project. I’ve made three moves since then, and I now find myself in yet another new city, ready and waiting to fall in love.

But my first Stockholm did become a beloved place for me. I found spots that I loved and things I loved about it. It took some digging, but that made them all the more special.

When it finally came time for me to move away, I was excited for a change, but I was also very sad to leave. It caught me off guard when I realized the things I would be sad to let go of. But then that made me so happy—that I had been able to make connections there. The grieving that comes with being uprooted was a bittersweet sign that I actually had been about to put down roots.

The creative legacy of confinement

But I left with more than just fond feelings. I’m still reaping the benefits that the Stockholm Project had on my creative development. It was rather like an incubator for ideas and skills, and I’m still working on projects that began there—with the hobbies and ideas and stories I collected there—not the least of which is this very journal.

No two experiences of confinement are the same, so I can’t say that I’ve got the solution. But I like to imagine that I’ve something in common with the unnamed artist from St. Walburga. Maybe she had conjured her images out of the air, but I believe it more likely that she simply took the time and the care to look more closely, to reach further, and to uncover what was hidden in plain sight and make it her own.