In 1830, Victor Hugo was at odds with his publisher. A book had been promised but Hugo had yet to complete the manuscript. So Hugo finally buckled down, got himself a fresh bottle of ink and dove in. A few months later, the bottle of ink was empty and the promised manuscript was finished. Hugo even considered titling it “The Contents of a Bottle of Ink.” But another title was chosen: “Notre Dame de Paris.”1This anecdote about the bottle of ink comes from “The Titles of Books” in Chambers’s Journal of Literature, Science, and Art, no. 366, 1870, and is, perhaps, a little too cute to be believed.

Yet this title too was cast aside—at least by the English publisher, who for some reason took the immense liberty of calling the novel The Hunchback of Notre-Dame. I don’t know why this was done—but I do know that it gives a very false impression of the book, which is, in fact, not about the Hunchback.

It is about the church.

Hugo wrote the novel in order to celebrate the Gothic cathedral, which was in peril, falling into disrepair and neglect.

And if the rightful title is not clue enough, the novel has long sections of description of the church’s architecture which have, no doubt, confused and irritated readers who showed up for a hunchback and got a lesson in fifteenth-century ecclesiastical architecture instead.

I have mixed feelings about this, to be honest.

On the one hand, writing a novel to save a Gothic cathedral is maybe one of the most beautifully romantic things I can even imagine. And I kind of wish I had thought of it first.2Seriously, don’t put it past me.

But on the other hand, it is a novel—a work of art. And it’s a risk, turning a work of art into a multi-use appliance, by giving it extra “jobs” to do—jobs besides being a work of art.

Of course, it’s not as if aesthetics and practical use are opposing forces.

On the contrary, the arts have been put to a great many practical, real-world uses. Typography and calligraphy balance legibility and aesthetics. Clothing runs the gamut of ultra utilitarian to artistically impractical, with plenty of room for function and fashion to play in the middle ground. And architecture is maybe the ultimate practical art. Really anything with the word design in it is some form of art with a job.

Then there is the massive realm of language, a world of usefulness and enjoyment all its own.

And stories have been used for entertaining and teaching, enlightening and instructing3That’s to name just a few of virtually <em>limitless</em> purposes. for probably almost as long as we’ve told stories.

Case in point: In Chapter 2 of Notre Dame, the poet Pierre Gringoire looks on as his morality play premiers for an open-air audience. Morality plays were a popular form of medieval entertainment and told allegorical tales, usually involving the protagonist meeting characters like “Justice” and “Labor” and learning a valuable (bet you saw it coming) moral along the way.

So use and enjoyment are not entirely incompatible, but I think the way you mix them makes all the difference.

And I’m not the first to suggest so.

The master of sentences categorizes everything

Medieval theologian Peter Lombard—the same “Pierre Lombard” whose book Claude Frollo is reading in Book V, Chapter 1 of Notre Dame—taught at the cathedral school of Notre Dame (about 300 years before the time of the novel’s setting), and concerned himself with the distinction between use and enjoyment, in his master work, the Sentences. He borrowed the idea from St. Augustine and used it to divide up everything4Yes, that’s right, everything. Medieval theologians didn’t do anything by halves. into three categories: there were

- things that should be enjoyed,

- things that should be used,

- and then things that may be both used and enjoyed.

And there were negative consequences of mixing up these things.

Peter wasn’t talking about art, but I think we all have experienced the unpleasantness of these things getting mixed up. Because even if use and enjoyment aren’t mutually exclusive in art, it seems especially difficult to do them both—well.

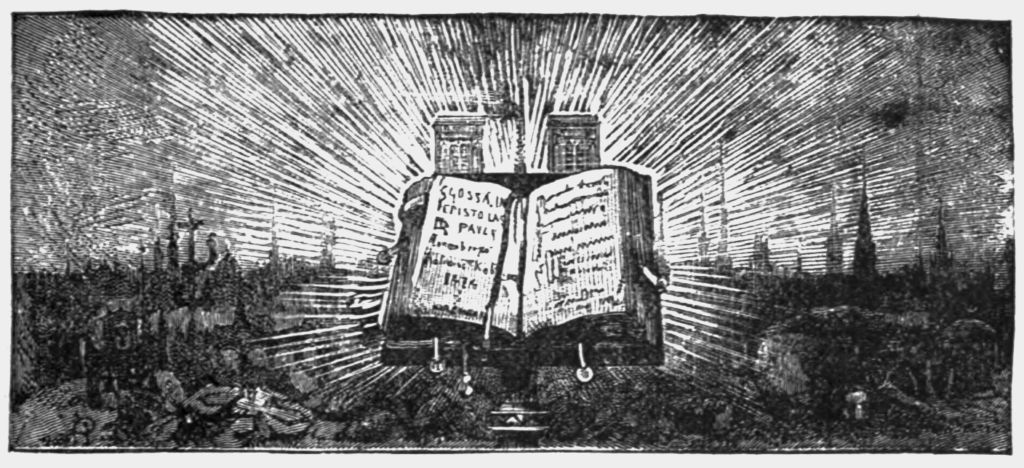

Figure 1. A graph illustrating relative usefulness and enjoyment

I charted it out and noticed a few things. First, obviously it’s hard to think of low-use/low-enjoyment things because—why would you bother. Second, it’s pretty easy to think of high-use/low-enjoyment things, as well as high-enjoyment/low-use things.

But the fourth quadrant is harder to fill.

Logically, if we wanted to fill out that upper right quadrant we could either take some high use forms and make them more enjoyable and aesthetically pleasing—this mostly means elevating the design so that it achieves the use, but with a bit of finesse

Or we might take a high enjoyment form and give it a purpose. This is so much harder (which is not to say that the first option is easier). And it’s harder for a few reasons.

What is it about multi-purpose art?

There are two major pitfalls, from what I can tell:

First, artwork with other motives can tend to be…not very good.

Take the morality plays, for example. Although they were popular in their time, I don’t think there have been many throughout history who would class any morality play alongside Antigone and Hamlet and Death of a Salesman in the dramatic hall of fame. I don’t want to disparage for being what they are–but what they are hasn’t stood the test of time all too well.

And I’ll let you add your own examples of works of art with lofty goals and mediocre results.

Second, these works of art can be very heavy handed…and off-putting.

Although Hugo seemed to pull off the near impossible by writing an excellent novel that people wanted to read and that served a purpose, he almost didn’t. The truth is that his novel-quest worked almost in spite of itself.

Hugo was a true master of his craft. And to a certain extent, when you have that kind of talent, you can make your own rules. But Hugo comes very close to failing at the novelist’s number one job: write a novel people enjoy reading.

Because of his mission. Because of all the architecture.

Even those who praise the novel question his architectural enthusiasm creeping around every corner:

“At times [Hugo] over-loaded his novels with technical details, apparently the result of special reading undertaken to obtain local color.…the architecture and history of the middle ages intrude in “Notre Dame” far beyond what is necessary to give the required color and atmosphere. As a work of art this novel would only be improved by the omission of the chapters on the topography of Paris and the architecture of the cathedral. Yet it cannot be denied that in “Notre Dame” he has written a story of tremendous force and enthralling interest.”5William Allan Neilson in the Biographical Note to Notre Dame de Paris by Victor Marie Hugo. Vol. XII. Harvard Classics Shelf of Fiction. New York: P.F. Collier & Son, 1917; Bartleby.com, 2000.

That’s the real twist in this story: Hugo set out to write a novel with a mission—a novel that would attempt to be a novel while also doing a job—but he achieved this mission at the expense of those passages where his mission is most apparent.

But thankfully those moments pass and the rest is about as good as a novel gets.

So what’s the secret?

So how is it that the best art does do more than just give enjoyment or look pretty—it can teach and inspire and maybe even create a national icon—but somehow those goals so often seem to hinder or cripple the work of art?

Why is it so hard to make good multi-purpose art?

I have two answers to give: one practical and the other mystical.

The first is expectations. Novels generaly look like novels and blueprints generally look like blueprints. So, if you start laying out blueprints for flying buttresses in the middle of your historical novel, people are going start wondering what the heck they just picked up to read. You’ve compromised your sincerity in some way that I don’t think artwork will allow.

My second answer goes back to the Lombard’s Sentences. Peter’s third category, things which may be both useful and enjoyable (and remember, Peter was not thinking about artwork), includes two beings: angels and humans. At first this seems irrelevant and un-useful for our purposes. But maybe not.

It’s easy to see why a human is useful—we’re capable of quite a lot—but for Peter humans were able to be enjoyed because they bear the image of God.

In other words, there is an essence of the Creator—the ultimate enjoyment—in humanity, which imparts value that needs no justification. It is a paradoxical absolute value that is not contingent upon any benefit.

And I cannot but think that art, in a much smaller way, is valuable for the same reasons.6I feel bound to point out that I am proposing that humans and artwork gain their value in a similar way—but by no means to the same degree. Just for clarity’s sake, I’ll emphasize: art cannot equal the value of a human being. Art, in a mysterious, magical way, has an absolute value that is imparted by the intrinsic value of its creator. It’s a paradox or a tautology or whatever you want to call it—but it’s the best answer I can give.

Notre Dame de Paris is still loved because it’s a novel, not because it helped to save a church. The latter makes it an amusing anecdote for cocktail parties but the former makes it a work of art.

It is magical because it did not need to help save a church in order to be valuable.

Art is valuable because it does not need to be useful. It is valuable because it is—not because it does.