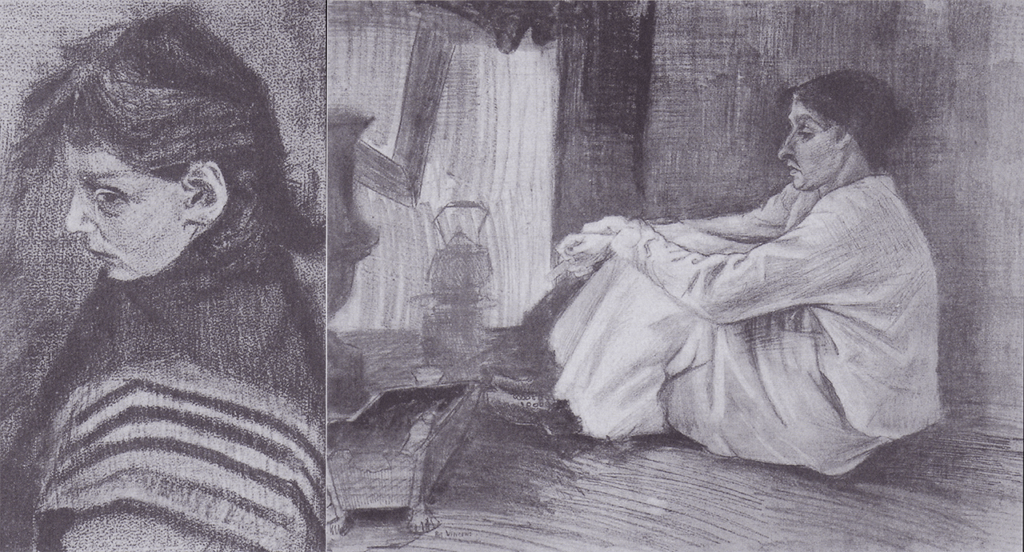

Throughout his life, Vincent van Gogh kept up a continual correspondence with his younger brother Theo. Theo was not only his brother’s confidant, but it was he who encouraged Vincent to focus full-time on his art and supported him financially so that he could do so. Theo heard about all of the highs—and many lows—of his brother’s troubled life and difficult career. These letters tell the story of the birth and growth of an artist—all of the inspirations, hard work, disappointments and self doubt.

The self doubt is especially palpable in a series of letters from the years 1881 to 1883. Vincent was in The Hague, finally free from the restrictions of his parents’ household and focusing full-time on his drawing. He was living among the poor, drawing inspiration from the daily life, the landscape, and the melancholy he saw around him. In his words it is clear Vincent felt a troubling discord between his inspiration and his work. In one letter to Theo, dated 1882, Vincent states,

“How I paint I do not know myself. I sit down with a white board before the spot that strikes me, I look at what is before me, I say to myself that white board must become something, I come back dissatisfied – I put it away, and when I have rested a little I go to look at it with a kind of fear. Then I am still dissatisfied, because I have still too closely in my mind that splendid nature.”

At this time Vincent was still a very young artist. It would be years before he would create his most celebrated paintings.

Greater self confidence surely came with experience, but few, if any, mature artists are able to fully outgrow dissatisfaction with their own work. Slews of artists have been bound and determined to destroy work that disappointed them. Whether expert or novice, I think the true source of this disappointment is just as Van Gogh describes: “I am still dissatisfied, because I have still too closely in my mind that splendid nature.”—the work pails in comparison to the vision.

Perfection is in the eye of the creator

When I first became curious to identify what exactly perfection is, I was rather underwhelmed by the definitions I found, such as you’ll find in Merriam-Webster:

- freedom from fault or defect : FLAWLESSNESS

- MATURITY

- an exemplification of supreme excellence

- an unsurpassable degree of accuracy or excellence

These and other words and phrases that come up—like “satisfying all requirements,” “proficient,” and “without fault”—just seemed to fall short. These were insufficient to describe this thing which has made me and so many other perfectionists feel so…insufficient. Perhaps I should be asking myself why even perfection isn’t good enough for me.

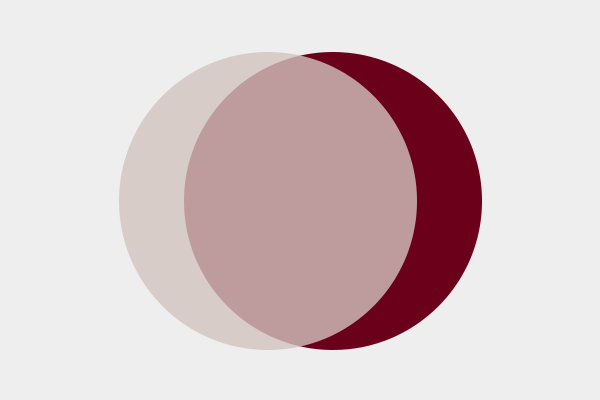

But I think the real issue is that none of these perfections—nor those I talked about in Chapter 1—is the perfection that keeps us awake at night and stalls so many projects. The perfection we really have in mind is the realization of a vision—that “splendid nature” which Van Gogh couldn’t let go of. We know what we want to create, but, for whatever reason, cannot realize it. This perfection is very, very specific with very little margin for error. Anything that is not the realization of the vision is imperfection. Unfortunately, it then follows that we are only satisfied with our work to the extent that it meets our expectations—all of our satisfaction and disappointment rests upon the variance of what we create and what we envisioned.

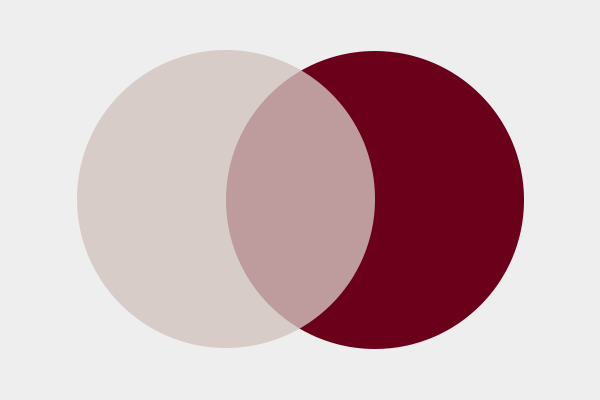

Figure 1. My actual work vs. my creative ideal

If I were to give a name to this type of “perfection”—the perfection in the eye of the creator, it would be Platonic perfection.

What’s Plato got to do with perfection?

I use the term “platonic”1The most common usage of the term “Platonic” in common parlance is denoting a relationship that is purely friendly, not romantic. For years I was confused by this. But the reason for this is Plato’s concept of “Platonic love,” which is a spiritual type of love which connects one to the universal, ideal, immaterial. While romantic love is physical, friendship is purely mental or spiritual, thus: Platonic. to reference Plato’s theory of forms. With this theory Plato explains the connection between ideas and things. According to the theory of forms, all material things in the physical world are less-than-perfect copies or manifestations of the immaterial ideas of those things (often referred to as “Platonic ideals”). The classic example given to illustrate Plato’s theory is the concept of a circle. According to Plato, we can understand the idea of an ideal, perfectly round circle, yet we will never be able to realize, to create a physical circle that perfectly embodies the ideal circle.2I’d be curious to hear what Plato’s response would be to learning about the computer software and such which now help artists, designers and engineers create precise physical shapes. Would he maintain that neither are these perfect reproductions? Yet the ideal circle is a thing, it exists and we can all acknowledge and understand it—we just cannot get to it.

I think we look at our creative visions in much the same way—the perfect work that we’ve imagined exists, it is real and recognizable—we just can’t seem to get to it. We are trying to create the “perfect circle” in our mind’s eye. And when you have this perspective, it is quite maddening to fail in reaching your goal—because the ideal does exist in your mind. This would explain why an artist can be whole-heartedly disappointed with their work, even as everyone around them offers sincere praise. Just like Van Gogh, you see imperfection because you can still see in your mind the ideal: “I am still dissatisfied, because I have still too closely in my mind that splendid nature.”

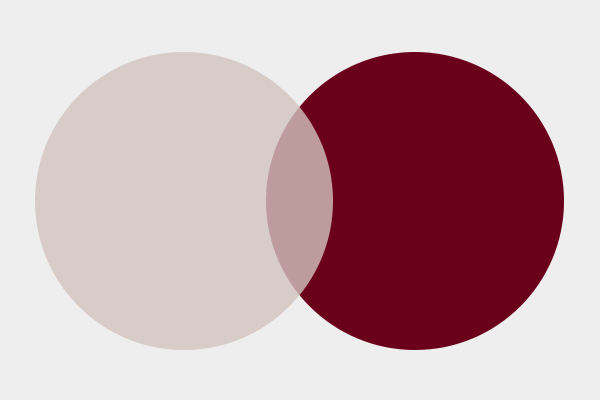

Figure 2. The effect of actual work vs. ideal variance on levels of disappointment

a.

b.

c.

A few problems with Platonic perfection

The first problem

The first problem with Platonic perfection is that it doesn’t exactly work in this scenario of creative work. This idea that you have is a real idea, but it is quite different from the idea of a circle. If there were no such thing as a circle, and you were inventing something called a circle for the very first time—it would not be possible for you to get it wrong. You are creating something that has never been before, so there can be no blueprint—that is what it means to create—that is why creativity is so special, and so hard. You are by definition, going somewhere no one has gone. Attempting to draw the perfect circle is attempting to realize something that everyone already understands—but artistic creation is about creating something that no one—not even yourself—has a true and clear conception of.

The second problem

The other major problem with this model is that it creates a very uni-directional way of thinking: you are moving in the direction of an ideal and that ideal is the only possible realization of success. And that’s not really how creativity works.

Even if you think about a piece of work that you admire and find absolutely perfect—nothing left out and nothing out of place—can you really say with all certainty that that is the only possible iteration of that project which could be successful? Can you really declare that there is no other possible way that that work could be as excellent as it is? It feels like you can say that, because this is the work that exists. But really, there is never only one right answer in art.

Embracing variation in music

For whatever reason, musicians seem to be much less married to the idea of the Platonic ideal than artists in literature or the visual arts.3This is only a personal observation, but I’d be curious to hear if a musician would concur. As for the visual arts, the closest parallel I can think of is a series such as Claude Monet’s Haystacks. But in literature, I can think of no parallel that would not be seen as lazy. Musicians seem to be much more comfortable with “iterative” art, where variance is embraced rather than reduced. Think of artists who release multiple versions of the same song, or of song remixes, or the many songs that are covered over and over by each new generation of musicians. But this is hardly a modern phenomenon: musical variations, like Rachmaninoff’s Variations on a Theme of Chopin, are essentially exercises in iteration, repeating a theme with slight variations. If there were truly only one “right” iteration of a piece of work, then all of these creative techniques would make no sense.

It’s pretty easy to recognize that all art is generative, growing out of and benefitting from the work of others, as these examples illustrate. But the point I’d like to emphasize here is that there is no one conclusion for your project. Platonic perfection gives the illusion that there is only one possible successful outcome for your project—the one that you have envisioned. But when you allow yourself to set aside that misconception, you can see that there is no one perfection in art.4I wonder, is this the same as saying there is no perfection in art? There are always many right answers in creative work, and there is no template for something that you have not created yet.

Many years after Jimi Hendrix covered his track “All Along the Watchtower,” Bob Dylan said,

“It overwhelmed me, really. He had such talent, he could find things inside a song and vigorously develop them. He found things that other people wouldn’t think of finding in there. He probably improved upon it by the spaces he was using. I took license with the song from his version, actually, and continue to do it to this day.”

I love how Dylan suggests something almost organic about the song. It had things inside of it that even he, the creator, did not recognize. And it continued to grow, in Hendrix’s cover, and as Dylan continued to perform the song in Hendrix’s style. Oftentimes, artwork can go on to grow in ways we couldn’t have expected, even after it is “finished.” It is yet another irony of this whole concept of perfectionism that some work will only develop further after we have taken the leap of calling it “finished.” So how do we know when we are finished? I can’t wait to come back to this intriguing question in the third and final chapter of this cycle.