Teenaged Claude Monet was a skilled caricaturist when he met landscape artist Eugène Boudin. Boudin recognized the young man’s talent, but urged him to be a bit more ambitious. Boudin invited Claude to go out him to paint en plein air—in the open air. He urged,

“Study, learn to see and to paint, draw, make landscapes. They are so beautiful, the sea and the sky, the animals, the people and the trees, just as nature has made them, with their character, their real way of being, in the light, in the air, just as they are.”1Claude Monet, from a translation of an interview by Thiébault-Sisson, published in Le Temps, Paris, 27 November 1900.

Monet liked the man, but did not like his paintings—and had no desire to go. But eventually he could no longer find excuses for Boudin, so he went.

And that experience changed the whole direction of the young artist’s career:

“Boudin, with untiring kindness, undertook my education. My eyes, finally, were opened, and I really understood nature; I learned at the same time to love it.”2Claude Monet, from a translation of an interview by Thiébault-Sisson, published in Le Temps, Paris, 27 November 1900.

Capturing things just as they air

Painting en plein air was not standard practice for most painters at the time—sketches might be made out of doors, but painting took place in the artist’s studio. In fact, it wasn’t even practically feasible to paint outdoors until the nineteenth century, thanks to tools like the paint tube, which was invented in 1841—just a year after Monet’s birth.3“Never Underestimate the Power of a Paint Tube” by Perry Hurt from Smithsonian Magazine. read it now.

Outdoor painting became a lifelong passion for Monet and a founding tenet of the Impressionist movement.

Inevitably, at some point Monet realized that if where one painted mattered, then so did when one painted.

He took to returning to the same spots over and over again, repainting the same vistas in varying weather conditions and at different times of the day or the year—to capture the changes that the light wrought on the scene.

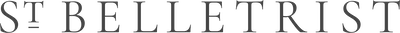

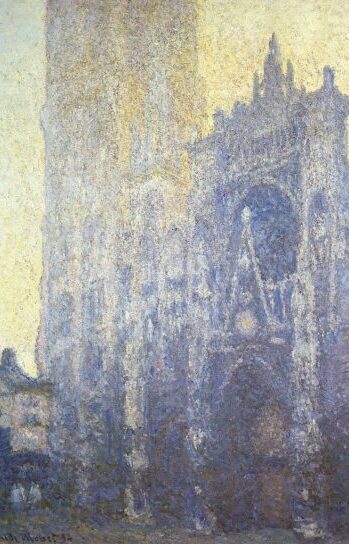

Monet completed several of these series throughout his career, including the Rouen Cathedral series.

The Rouen Cathedral Series, Claude Monet (1892-1894)

Monet went to great lengths to capture a time and a place—

setting up to paint on a floating dock, digging trenches to stabilize his easel, even persuading officials to delay the departure of a train at the Gare Saint-Lazare station.

But I didn’t really begin to appreciate Monet’s quest to be at the right place at the right time until I had my own experience chasing the light—but not with a paint brush.

Drawing with light

Painting isn’t the only way to capture light. Interestingly, around the same time that Monet and the Impressionists were learning to paint light in the moment, another art form (and technology) was growing in popularity—an art form that made capturing light in a moment in time and rendering scenes of nature “just as they are” possible in a new and incredible way. In fact, this art form didn’t just seek to paint the light, it drew with the light—or at least that’s what the word photography means.

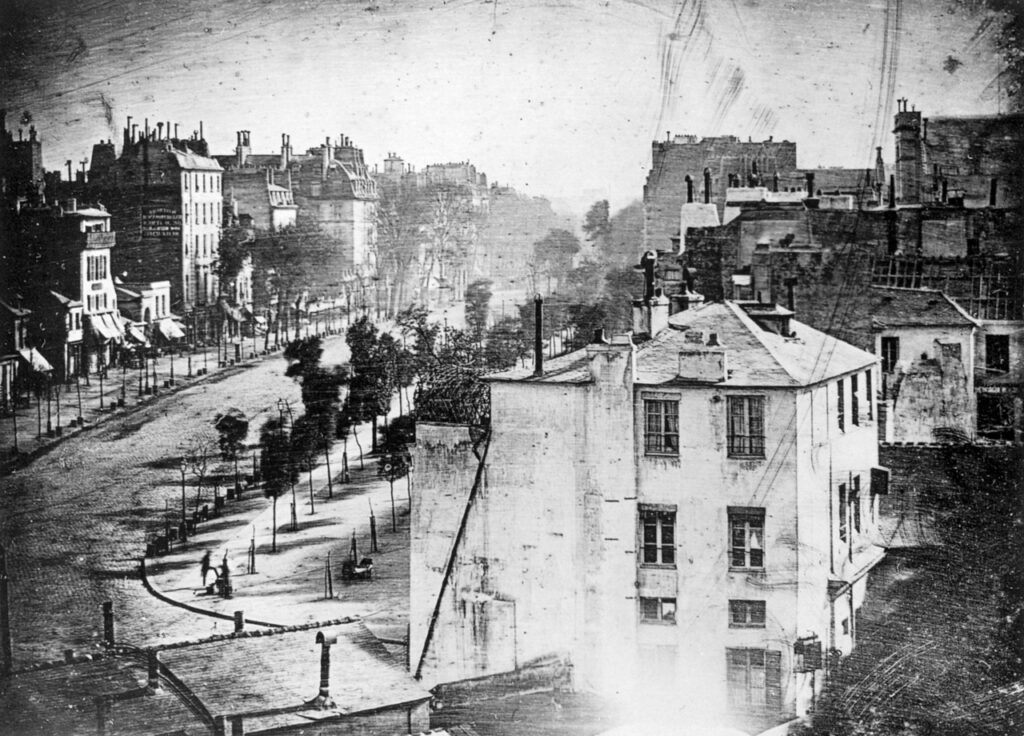

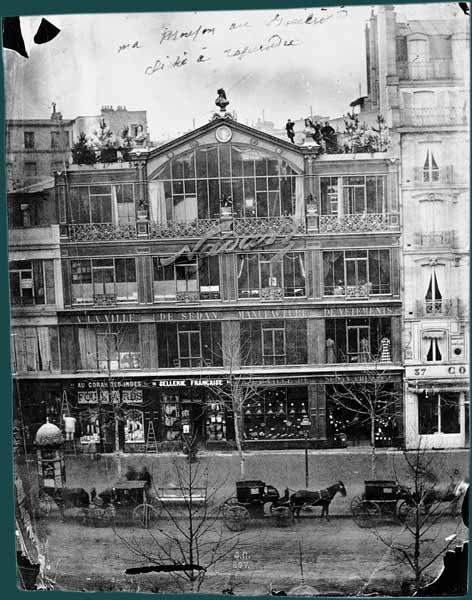

The development of photographic technology was a long process of trial and error which multiple experimenters and inventors contributed to. And several of these figures were countrymen of Monet’s, including Nicéphore Niépce and Louis Daguerre. Daguerre was the photographer of what is believed to be the earliest surviving photograph of a person: Boulevard du Temple which was taken in 1838-39 in Paris—birthplace of Impressionism.

In fact, the landmark 1874 Exhibition of the Impressionists, which premiered work by Monet, Boudin, and the core figures of Impressionism, took place in the studio of photographer Nadar, who pioneered aerial photography.4Sadly, Nadar’s aerial photographs have all been lost, but he liked to take studio self-portraits in his hot air balloon–which are absolutely priceless.

Chasing the light

As I mentioned in a previous entry, during my adventure in idle valley I picked up film photography. But this is actually a rather grandiose term for buying a camera online, wasting two rolls of film in pitiful attempts to figure out how to use it, and then tossing it on a shelf for a year or two.

The camera is a bare-bones SLR that comes in a kit which you assemble yourself. It was easy enough to assemble. Unfortunately, the instructions ended at the point that the camera was put together. After the two wasted rolls, I absent-mindedly set it aside, intending to actually figure out how to take a picture at some point.

Then I moved to a beautiful city by a river—a city full of beautiful old buildings. I was inspired to pull the camera off the shelf and finally figure out how to take a picture.

It is positively magical, what a plastic box of mirrors and glass can do.

But it has its limitations. Oh is it ever limited.

There’s a very important ingredient for a photograph that was not included in the kit: light. Loads and loads of light.

After I developed the first successful roll of film I learned an important lesson: in order to capture anything at all, a lot of light is required.

It’s an incredible limitation that I had never had to work with before. It sounds simple enough to deal with, but the need for light led to other complications: There were also time and space constraints. I couldn’t shoot indoors (with any reliability) and I couldn’t shoot in the shade.

This restriction was just so different than any other creative medium I had ever worked in. There just weren’t many restrictions I had been forced to comply with.

You can write virtually any time or place. All you need is a laptop, or table, phone, or pen and paper, pencil and napkin, crayon and old takeout menu. You give me a marker and I’ll do just fine on my arm.

And for just about any other medium, electricity eliminates any restrictions.

Not with photography.

But the limitations were actually sort of inspiring. It made me look at the world in a whole new way.

It was a challenge. It felt like a game.

My success rate with the camera still wasn’t great, but I soon made plans for a new project incorporating film photographs of my favorite places in the city.

But then the game changed just a bit.

The race against the dying of the light

I was moving away from the city by the river in five months. Subtracting the rest of the spring semester, that meant I would have only the summer to collect all of the photos I needed.

I had a list of ten locations to photograph.

Ten spots in three months seemed doable enough. But the time began dwindling away at an alarming rate. I had the summertime daylight on my side, but there are only so many hours of sunlight in a day. And then I had to subtract about an hour after sunrise and an hour before sunset, when the light just wasn’t enough. Then I tried to avoid the midday hours (because, summer in the South). And any overcast or rainy day was out.

I’ve never paid so much attention to the weather in my life. Thankfully, I had the luxury of planning my schedule around the weather.

But time was only the half of it. There was also space to deal with.

Some places are more crowded on weekdays than weekends. Other places start losing light sooner, because of trees or hills. The hardest to catch were the locations in urban areas. The closely packed, multi-story buildings blocked out light. I went back to the same spots multiple days at slightly different times, trying to find the right window.

One of the last locations I shot was a pair of rather narrow intersecting streets lined with mostly three- to five-story buildings—that seemed absolutely impervious to sunlight for all but a few hours a day.

In the end, I got all of the locations on my list and almost all of the shots I wanted.

These images are to be accompanied with words—words that I still haven’t finished writing—over a year later. Writing is almost never something I am unable to do—in and of itself. Any time, day or night, I have the tools at hand—several times over.

But because of that, there’s no urgency. I’m not beating myself up for that and I’m not blaming my own procrastination on the circumstances—but I’m also very sure that if I still lived in the city by the river, I would still not have visited all ten locations with my camera. I was lucky that circumstances left me with enough free time to pursue a side project that summer, but it was the very imminent closing of that window of time that made me take advantage of it.

Any more constraints and it probably wouldn’t have happened. But any fewer, and I may not have tried. It was a very mundane sort of magic, that made me take notice of the setting of the sun, of where I was, and for how little time.

Welcome to cloud town

My summer chasing the light has become quite a poetic thing to me, because I didn’t know then that I was moving to a place that sees much less of the sun. I moved northward, and up here we get hand-me-down clouds from the Great Lakes.

The clouds don’t directly affect my daily schedule, but it’s cloudy enough here that there are actually physical and mental effects from the lack of sunlight. And it’s cloudy enough that I’ve learned to notice the sunlight when it comes.

A few weeks ago I noticed the sun was had come out—just about an hour before it was to set. So I took a walk, I set out in the direction of the light, to take a moment, to appreciate the sinking sun in Cloud Town, while it’s here and now.