It is no small thing for a creator to have his or her work recognized by a contemporary audience—let alone to achieve lasting posthumous fame. But what is perhaps even more remarkable is to attain all of this reluctantly.

Amazingly, Emily Brontë did all of this in her very short life and even shorter career. But then, there was almost nothing typical about Emily—or her family.

Emily just wants to be left alone

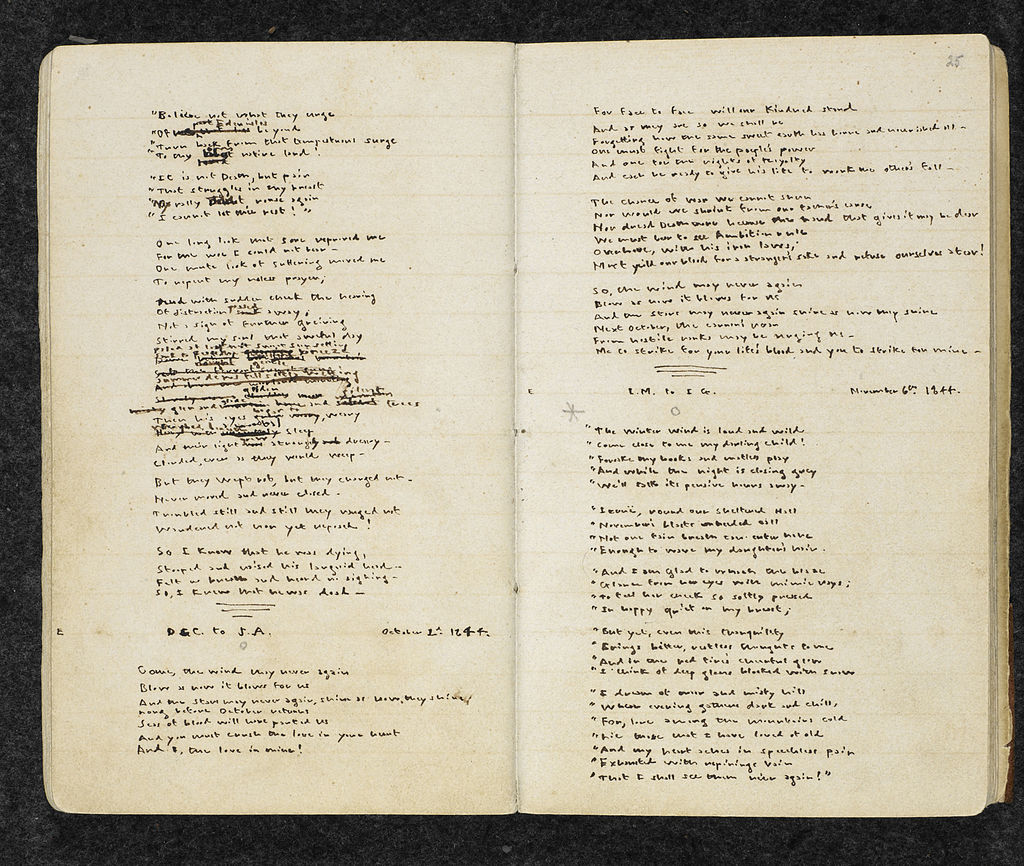

The three writing Brontë sisters chose to seek publication for primarily financial reasons. But Emily did not readily agree to the plan—she had been furious when her sister Charlotte had discovered her hidden stash of poems—and she took some convincing.

Emily had all the talent of Charlotte and Anne, but seemingly none of the worldly aspirations. Still, after the poems Emily published her only novel, Wuthering Heights, which single-handedly immortalized her in the canon of English literature.

Yet without her sisters’ intervention, Emily would have been perfectly content to write in private for her entire life—at least, as far as we can tell. Emily Brontë is an extreme case, to be sure, but excessively secretive writers are not entirely uncommon.

Reclusive writers anonymous

English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote in secret and achieved only posthumous fame for his very unconventional style of writing. As a Roman Catholic priest, Hopkins wrote in secret because he couldn’t seem to quit altogether, but a literary career seemed inappropriate for a priest.

Emily Dickinson’s enormous reputation rests on close to 1,800 poems which were found by her sister after Emily’s death—rather than the meager ten published during her lifetime. She seems to have had conflicting feelings about her own desire to publish.

And J. D. Salinger, who had a very successful literary career, stopped publishing entirely in 1965, but continued to write for the remaining fifty years of his life—all of these later works as of yet, unseen by the world at large.1We are still waiting for Salinger’s widow and son to finish sorting through his papers and to begin publishing these works.

Although I could name off a few more secretive authors, I made a quick search for creators in other fields who kept their work hidden, but I came up short. I’d love to know if there are any out there, but then again, hiding a sculpture or canvas, for example, poses some logistical challenges unlike a manuscript. A closet is much more conducive to writing, than to other arts.

So I don’t know that the desire for secrecy is unique to writers, but, as a writer, it is something I can very much relate to.

A writing closet is bigger on the inside

I started writing for my own enjoyment around age eleven or twelve, and I relished doing so in secret. It didn’t feel like hiding, but rather opening up the freedom for myself to explore and experiment.

And as I got older, the privacy began to feel like a real luxury—because the first thing you learn in composition class is that you have to write for your reader. One of the cardinal rules of composition is to know your audience. It’s what I learned, and it’s what I will continue to teach my English 101 students. But as I was learning how to write for my reader in school, I all the more enjoyed writing for no one at all in my free time.

My creative process (2002–2019)

step 01

Quietly get inspired.step 02

Research and brainstorm in private.step 03

Draft and edit in secrecy.step 04

Store away in a special hiding place, for later perusal.Still, it can be a hard principle to defend—that it is actually possible to write for no one but yourself—yet I held to it for years.

But then I began to notice something strange happening.

In all those years of closet writing, every once in a while I would be crafting a scene, a plot, a character, and I would suddenly be reminded of someone I never consciously gave consideration to: the reader. I would find myself asking, “Does this make sense?” “Have I sufficiently explained that?” But for who?

When you’re writing purely for your own enjoyment and in secrecy, there is only one reader—you. But that wasn’t who I was thinking of. Rather, it was a sort of hypothetical reader. What would they take away from this scene? How would this character come across to them? What words could I use to properly convey the right mood or emotion to them?

It was amusing and perplexing to me. But I later heard a statement made by Ansel Adams that seemed to express what I was experiencing:

Adams is talking about a different medium entirely, but is the same true of writing? Is that second person always there—however immaterial or hypothetical they may be?

Does telling a story necessitate the pretense of a reader?

I’ve since learned that narrative theory has answered this question. And we have narratologist Wayne Booth to thank for naming this anonymous person: the “implied reader.” But even before I knew this name, this person caused me to question whether my philosophy of writing—or creativity in general—was not mistaken.

To share or not to share

I began to consider whether stopping short of sharing one’s work was to negate a fundamental component of the creative process—something I had always viewed with great reverence.

I had always considered diffusion of one’s work as an unnecessary optional step and, if I’m being honest, a presumptuous and insupportable declaration that I believed I had said something worth hearing.

But here I ran into a rather large hole in my logic. I considered my favorite authors, such as Charlotte Brontë, sister of the aforementioned Emily.

Charlotte also wrote alone in the privacy of her home for years, and then spear-headed the publication effort for the three sisters.

Did I consider Charlotte, who had little or no affirmation of her talent, presumptuous for her ambition? No, not at all. So, there had to be a way to share work without assuming some presumption.

And I found the solution in my reading—specifically, the Romantic poets.

Romanticism is for everyone

Romanticism was an aesthetic movement in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. One of its major premises was (in a nutshell) the value of the individual human experience in and of itself.

Previously, human experience was generally3A few pre-Romantic exceptions to this are Shakespeare’s comedies, which often featured a secondary plot involving servants, shepherds and clowns, alongside the nobles in the primary plotline, and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, which included a motley crew of characters from all walks of life, mostly members of the middle class. But even these examples do not value individuality and the uniqueness of each human experience in the same way the Romantics did. only valuable in literature if it told of a great and lofty figure or if it related something great and lofty. But the Romantic poets reveled in describing the common and everyday and in expressing their own individual experiences of love, nature, and beauty.

For example, William Wordsworth’s very famous poem, “Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey…” delights in the natural beauty surrounding the ancient abbey. But the poem is not really so much about the natural beauty as it is about Wordsworth’s mental and emotional experience of remembering and then revisiting the place. And it is this sort of experience and expression which was intrinsically valuable to the Romantics.

Thus, the writer is not deserving of a reader because he or she is uniquely superior, but because we are all alike individuals.

So, the act of sharing one’s work is not a declaration of a superior right to be heard—but of an equal right to speak.

And I realized that even if I had not the confidence of having something worth hearing, I may still have the conviction of having something worth saying—something worth allowing to be heard.

I have a deeply held belief that created things take on a life of their own, independent of their creators. Even so-called “dead documents” are still ever living—we talk about them in the present tense. “The plot is…” “Dr. Frankenstein is…” Even the authors, however long gone, are kept present in them: “Mary Shelley states…”

The work

There are projects I’ve worked on which, however much I doubt my own abilities to execute them, I have never doubted them.

And so, I began to feel that, rather than denying myself recognition or depriving a would-be audience, by refusing to share my work, I was actually dishonoring my work and the creative process that I value so highly.

If I sound overly dramatic in talking about this, I am okay with that, because I’m in the process of finding a new balance. In the interest of full disclosure, this journal is part of my own solution—a sort of exposure therapy for my reclusive habits.

This journal is my way of expressing and processing my own conviction in the work and the creative process.

I cannot promise it was executed well, and I cannot promise it is worth reading. I can only say that it has been worth writing—and incidentally, as I’ve learned, things worth writing are, every so often, worth reading.

Excellent! So smooth, elegant and insightful.

I’m totally jealous or your implied reader. 🙂